Oratoire Saint-Joseph

A Place of Signs and Wonders

by Evelyn Reid

Originally published on About.com

April 18, 2010

A pilgrimage site for Catholics in search of healing and support, Montreal’s Oratoire Saint-Joseph is one of the city’s leading attractions, a site where allegedly thousands of miracles have occurred in connection with a monk sainted by the Vatican.

For some, visiting St. Joseph’s Oratory is a life-changing experience.

Photo by Benjamin w lam (CC BY-SA 3.0)

“Put yourself in God’s hands; he abandons no one.”

-BROTHER ANDRÉ

Photo by Flickr user Sandra Cohen-Rose and Colin Rose (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Select pilgrims drop to their knees to climb 99 of St. Joseph’s Oratory’s 283 stairs in prayer, an unpleasant gesture done to symbolically share in the pain of Jesus Christ’s suffering on the cross prior to his death and resurrection, events believed true by millions of Christians worldwide.

However, and in the spirit of its saintly founder Brother André, the St. Joseph’s Oratory opens its doors to not just Roman Catholics but to anyone of any religion or belief system, welcoming two million people a year, including the more secular-minded primarily interested in the grounds’ architectural highlights, including its Italian Renaissance style basilica.

Among its notable features is the third largest basilica dome of its kind in the world after St. Peter’s in Rome and the largest one of all, Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro in Ivory Coast, a St. Peter’s tribute

And at 124 meters (over 406 feet) high, the St. Joseph’s Oratory’s basilica is taller than comparable structures,

including St. Patrick’s in New York, St. Paul’s in London and Notre-Dame in Paris.

The Oratory even trumps the cityscape: resting on Mount Royal, the St. Joseph’s Oratory cross represents the highest point in Montreal at 263 meters (863 feet) above sea level, higher than the mountain itself.

How Saint-Joseph’s Oratory Came to Be: The Miracle Man of Montreal

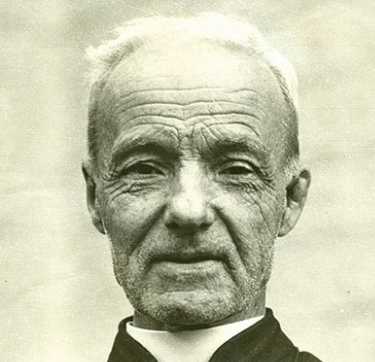

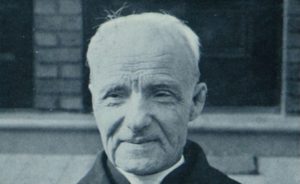

The story of Oratoire Saint-Joseph’s making reads like a fairy tale. Against seemingly insurmountable odds, Montreal’s most impressive structure was founded by, of all people, a low-ranking, illiterate, and uneducated orphan. And this humble orphan was linked to thousands of spontaneous healings and unexplained phenomena from 1875 through to his death in 1937.

Better known as Brother André, the eventually canonized saint came to be nicknamed the miracle man of Montreal in his lifetime.

Unfortunately, he didn’t live to see the Oratory’s completion in 1967, thirty years after his death.

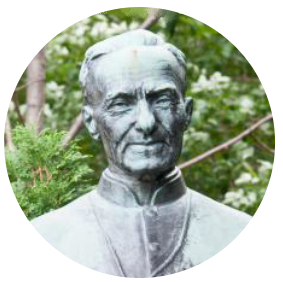

But his spirit lives on throughout the grounds as do his remains, with his heart embalmed and encased in glass in the Oratory museum and his tomb on display in a special chamber near the Votive Chapel’s 10,000 vigil candles. It’s not uncommon to see the devout laying their hands on his tomb in intense prayer, each waiting their turn for a chance to connect with the saint since at most three or four people can fit by his side at one time.

Evidence of Brother André’s Vatican-endorsed miracles—abandoned crutches and wheelchairs belonging to people who were reportedly cured on the spot—is scattered throughout Oratory grounds.

In warmer months, visitors trek through the Oratory’s outdoor Garden of the Way of the Cross which revisits the final moments of Jesus Christ’s life before his death on the cross and then subsequent ressurection as described in the New Testament.

Consult Oratoire Saint-Joseph’s website for more information on visiting the grounds and for an updated schedule of services, including mass in the frankincense-scented crypt church sharing floor space with the Votive Chapel’s thousands of vigial candles.

“There is so little distance between heaven and earth that God always hears us. Nothing but a thin veil separates us from God.”

-BROTHER ANDRÉ

“It is with the smallest brushes that the Artist paints the best paintings.”

-BROTHER ANDRÉ

Oratoire

Saint-Joseph

A Place of Signs

and

Wonders

by Evelyn Reid

Originally published on About.com April 18, 2010

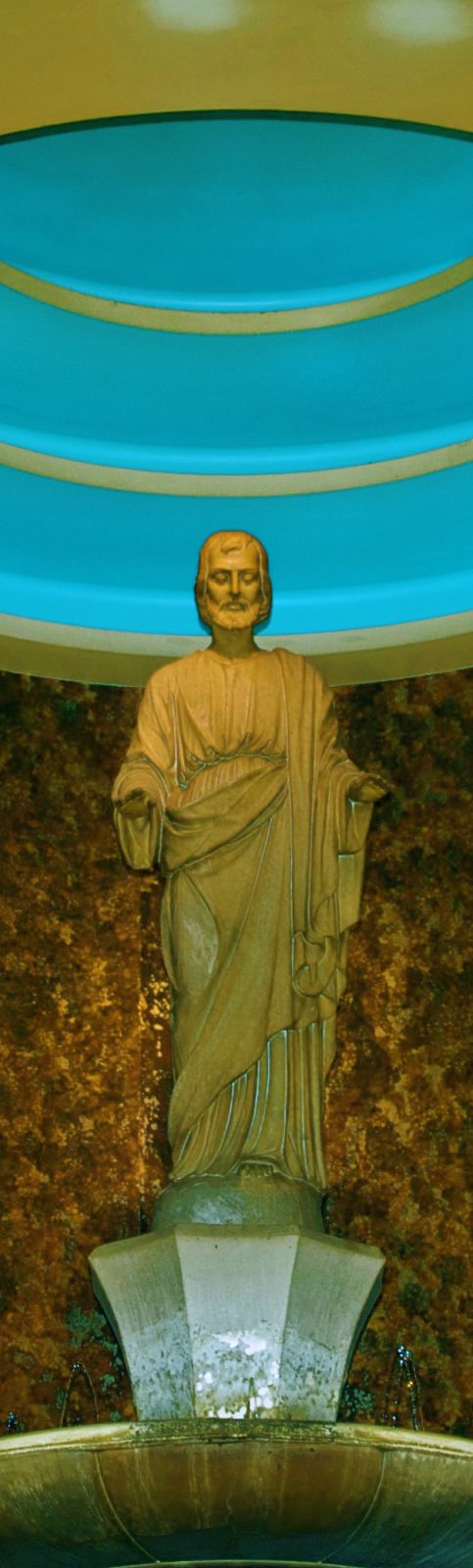

Photo © Clint Lewis

A pilgrimage site for Catholics in search of healing and support, Montreal’s Oratoire Saint-Joseph is one of the city’s leading attractions, a site where allegedly thousands of miracles have occurred in connection with a monk sainted by the Vatican.

For some, visiting St. Joseph’s Oratory is a life-changing experience.

Photo courtesy of Sharmidy (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Select pilgrims drop to their knees to climb 99 of St. Joseph’s Oratory’s 283 stairs in prayer, an unpleasant gesture done to symbolically share in the pain of Jesus Christ’s suffering on the cross prior to his death and resurrection, events believed true by millions of Christians worldwide.

However, and in the spirit of its saintly founder Brother André, the St. Joseph’s Oratory opens its doors to not just Roman Catholics but to anyone of any religion or belief system, welcoming two million people a year, including the more secular-minded primarily interested in the grounds’ architectural highlights, including its Italian Renaissance style basilica.

Among its notable features is the third largest basilica dome of its kind in the world after St. Peter’s in Rome and the largest one of all, Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro in Ivory Coast, a St. Peter’s tribute.

And at 124 meters (over 406 feet) high, the St. Joseph’s Oratory’s basilica is taller than comparable structures,

including St. Patrick’s in New York, St. Paul’s in London and Notre-Dame in Paris.

The Oratory even trumps the cityscape: resting on Mount Royal, the St. Joseph’s Oratory cross represents the highest point in Montreal at 263 meters (863 feet) above sea level, higher than the mountain itself.

How Saint-Joseph’s Oratory Came to Be: The Miracle Man of Montreal

The story of Oratoire Saint-Joseph’s making reads like a fairy tale. Against seemingly insurmountable odds, Montreal’s most impressive structure was founded by, of all people, a low-ranking, illiterate, and uneducated orphan. And this humble orphan was linked to thousands of spontaneous healings and unexplained phenomena from 1875 through to his death in 1937.

Better known as Brother André, the eventually canonized saint came to be nicknamed the miracle man of Montreal in his lifetime.

Unfortunately, he didn’t live to see the Oratory’s completion in 1967, thirty years after his death.

But his spirit lives on throughout the grounds as do his remains, with his heart embalmed and encased in glass in the Oratory museum and his tomb on display in a special chamber near the Votive Chapel’s 10,000 vigil candles. It’s not uncommon to see the devout laying their hands on his tomb in intense prayer, each waiting their turn for a chance to connect with the saint since at most three or four people can fit by his side at one time.

Evidence of Brother André’s Vatican-endorsed miracles—abandoned crutches and wheelchairs belonging to people who were reportedly cured on the spot—is scattered throughout Oratory grounds.

In warmer months, visitors trek through the Oratory’s outdoor Garden of the Way of the Cross which revisits the final moments of Jesus Christ’s life before his death on the cross and then subsequent ressurection as described in the New Testament.

Consult Oratoire Saint-Joseph’s website for more information on visiting the grounds and for an updated schedule of services, including mass in the frankincense-scented crypt church sharing floor space with the Votive Chapel’s thousands of vigial candles.

Learn more about Brother Andre's Life and Miracles.

The story of a pint-sized, illiterate doorkeeper who set in motion the construction of one of the world’s most impressive religious structures starts with a series of miracles believed true by millions.

Brother André—born Alfred Bessette on August 9, 1845 in rural Mont-Saint-Grégoire 50 km southeast of Montreal—was a living legend before the turn of the 20th century. Yet it’s not entirely clear how his mythical status started, let alone who was the first to claim Brother André changed his or her life.

What we do know is thousands of Catholics and non-Catholics flocked to Notre-Dame College in Montreal in between 1875 and 1904 to meet a doorman who reportedly healed the sick through prayer and touch, a five-foot tall monk who spent thirty years juggling janitorial work with miracle-making, an orphan almost rejected from the congregation he would come to serve for 40 years over concerns his chronic stomach problems and headaches would be a burden.

Tales of spontaneously healed smallpox and cured tuberculosis, heart disease, and cancer rumored to occur after visiting the diminutive monk baffled physicians. Some doctors went as far as to write letters to Brother André’s congregation affirming their inability to explain patient remission.

But while a trail of abandoned crutches and wheelchairs grew in Brother André’s healing wake, he maintained that he had nothing to do with these thousands of “cures”—”I have no gift nor can I give any,” he said—and yet, he was treated like a saint by the masses, including by women who, according to biographer Micheline Lachance, were not Brother André’s favorite gender. Keeping with the mores of his time, Lachance claims the fairer sex “got on his nerves.”

Regardless, praises multiplied at the turn of the century and as the years went by, Brother André’s reputation spread beyond the borders of Canada, enticing yet larger numbers of visitors to show up at the College’s doorstep, begging for a miracle.

But not everyone was in awe.

As pilgrims grew in number, so did his congregation’s contempt, concerned that Brother André would embarrass them. Select superiors felt compelled to point out that his uneducated, servant status did not entitle him to offer spiritual guidance, reminding André to keep rank. To them, his role was to do dishes, wash floors, fetch laundry, and answer doors, not heal the sick, much less inspire reverence.

But a significant chunk of the public didn’t seem to care what he did during his day job. They kept coming in droves, asking for his counsel, compassion, and alleged healing touch. And in the midst of his congregation’s attempts to thwart his mission, Brother André kept his head down, silently accepting criticism, scorn, and humiliation while refusing to ignore pleas for prayer sent his way.

The influx of visitors lingering around the college came to become a problem, so much so that the lineups disrupted school operations, irritating students’ relatives. Requests were so numerous that it took six to eight hours of Brother André’s day, every day, just to get through them all.

Brother André thought up a solution. To drive traffic away from Notre-Dame College, he invested the little money he had to erect a tiny, roofless chapel across the street from the school with the help of his supporters in 1904. The chapel, erected on Mount Royal, was built in honor of St. Joseph, the saint Brother André thought was the real channel of these miracles, miracles he called “acts of God.” Consistently invoking the husband of Virgin Mary in his appeals for healing, in Brother André’s eyes, he himself was, at most, “St. Joseph’s little dog.”

In concert with Brother André’s congregational detractors, health authorities eventually got involved, launching an inquiry in 1906 to get to the bottom of all these “miracles.” After all, not everyone believed anything miraculous was happening, accusing the monk of conning the public.

But their complaints fell on deaf ears. Montreal’s Archbishop Bruchési took no disciplinary action against Brother André even though it was requested by his own congregation. Rather, Bruchési wanted to watch Brother André’s evolution. The health inquiry was also eventually dropped. It seemed as though nothing could stop the orphan monk from pressing on. And by February 26, 1910, Brother André’s chapel received the blessing of the Pope. And that’s when Brother André’s “lowly” status changed permanently.

He was released from a lifetime of drudge work, of errand boy/housekeeping duties, given free reign to devote himself to his mission full-time, finally earning the right to preside over an oratory his own order originally opposed. And so persisted the expansion of what was once a small, roofless chapel into one of the most beautiful religious sites in the world, St. Joseph’s Oratory.

From a sickly, lowly, “burdensome” laborer to a miraculous minister who inspired the creation of the highest point in Montreal, little did Brother André know his beating heart would one day be encased in glass at St. Joseph’s Oratory for millions to contemplate. Little did he expect that 10 million faithfuls would petition for his canonization and that the Church would hold his character personally responsible for the devotion he evoked in life, and in death.

From a sickly, lowly, “burdensome” laborer to a miraculous minister who inspired the creation of the highest point in Montreal, little did Brother André know his beating heart would one day be encased in glass at St. Joseph’s Oratory for millions to contemplate. Little did he expect that 10 million faithfuls would petition for his canonization and that the Church would hold his character personally responsible for the devotion he evoked in life, and in death.

In 1982, the Vatican declared him beatified. And as of October 17, 2010—more than 70 years after Brother André passed away at the ripe old age of 91 on January 6, 1937—the miracle man of Montreal was officially immortalized in history books as a saint.