George A. Romero

The Zombie Godfather

by Evelyn Reid

Originally published on About.com September 9, 2014

Name drop “George A. Romero” on any given day and anticipate chatter of zombies to follow suit. Yet if you ask the “zombie godfather” his take, he’ll tell you he never set out to have his undead concept infect pop culture so pervasively, if the proliferation of urban zombie walks, zombie video games, and a wildly successful primetime series are any indication that the zombie apocalypse is here to stay.

If anything, he’s concerned the notion of a reanimated corpse schlepping along is a tired narrative. “I used to be the only guy in the playground,” he said in a 2013 Telegraph interview entitled “Why I Don’t Like The Walking Dead.” His disappointment vis-à-vis the horror drama series is no secret. Whether the let-down is fueled by the fact that Romero barely earned a penny from his opus of opuses due to a copyright fumble that catapulted Night of the Living Dead into the public domain decades before its time is possible and plausible, however speculative.

So on the eve of his Montreal Comiccon appearance, I sat down with the writer/director for a session of proverbial brain picking, if only for the chance to see today’s film industry through the eyes of a film legend who lived to tell the tale of the golden age of horror.

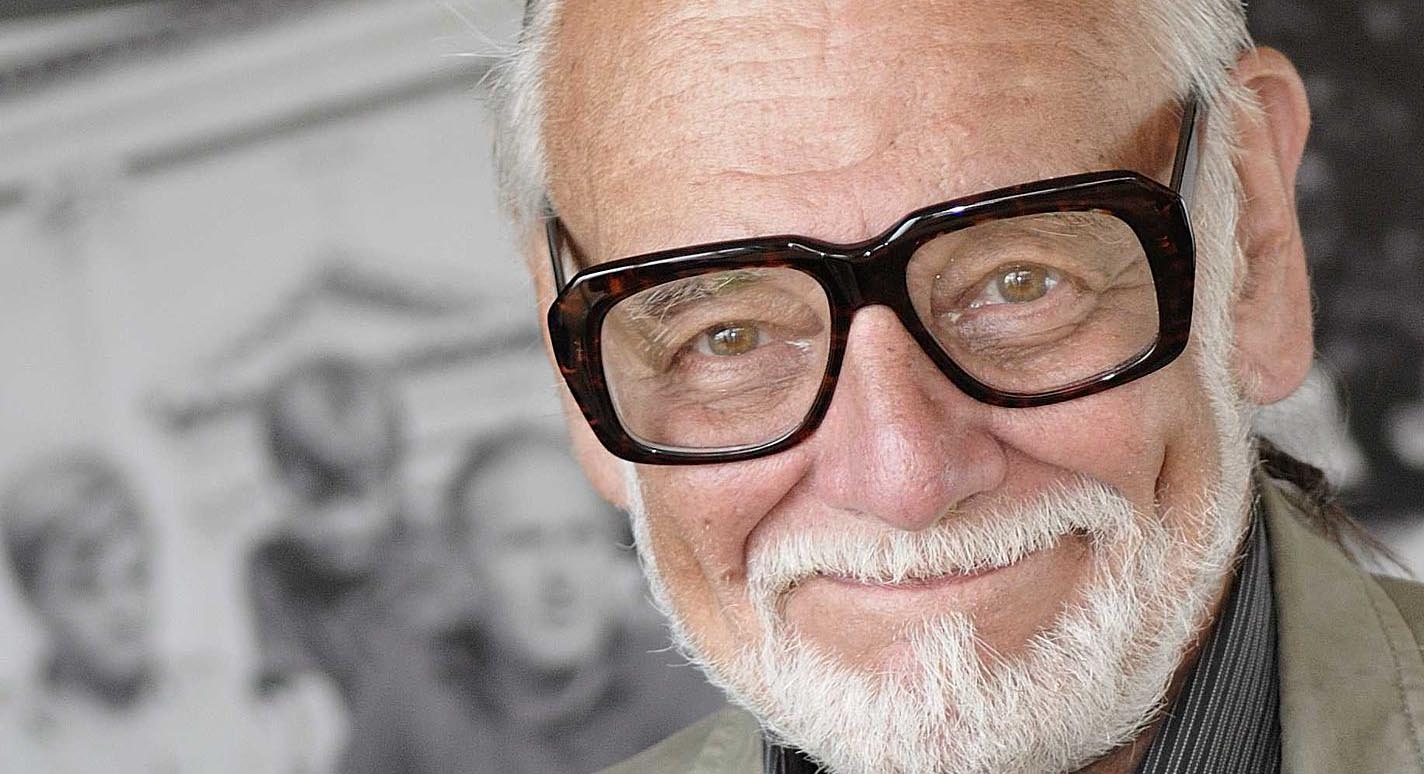

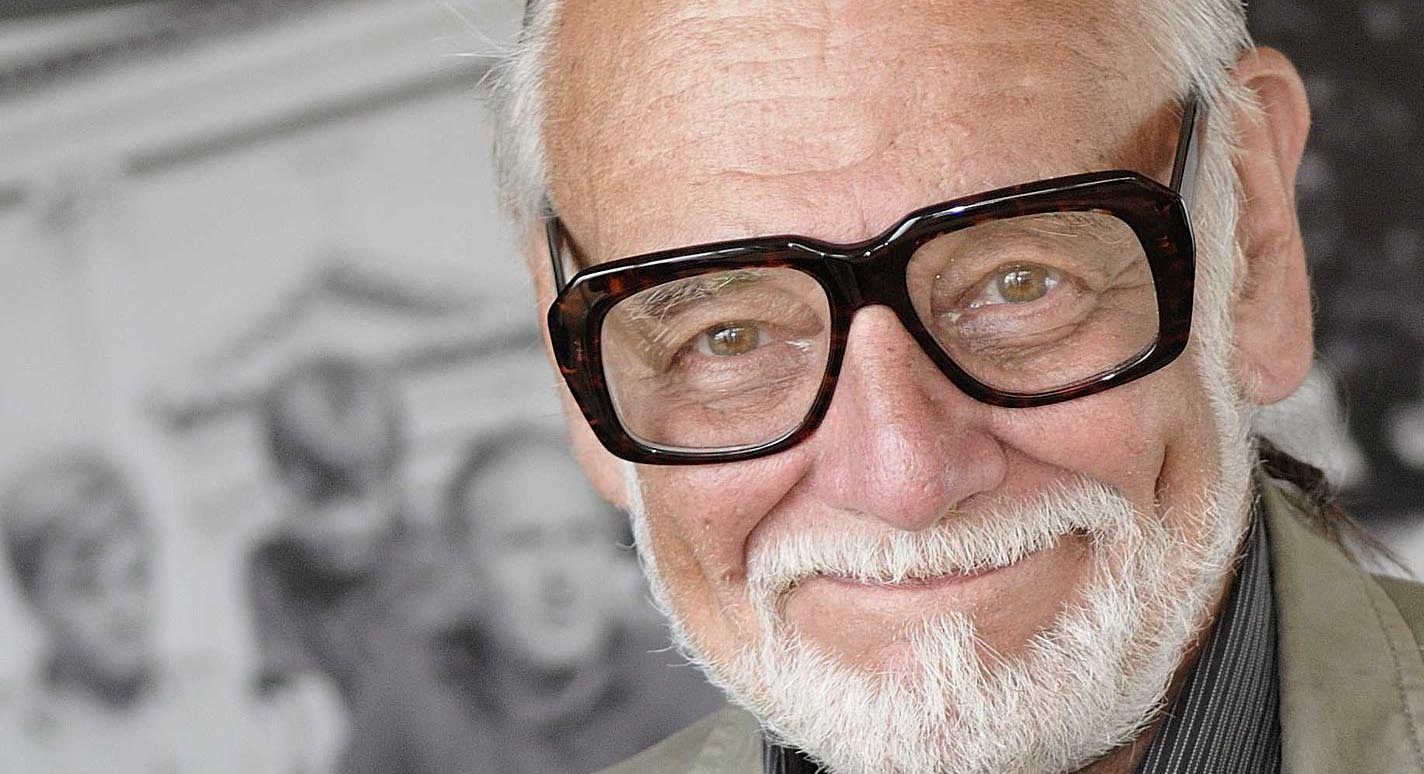

Above: George A. Romero (photo courtesy of George A. Romero). Top header photo: “zombie” participant at the 2013 edition of the Montreal Zombie Walk (photo by Flickr user Franck BLAIS (CC BY-SA 2.0)).

Evelyn Reid: You know, I wasn’t into zombies growing up. Apart from those featured in Michael Jackson’s infamous “Thriller” video, they did nothing for me. I found them boring and mindless, no pun. Then one day in college a friend wanted to show me a movie, a zombie flick. I looked at her, discouraged, saying, “you’d have to pay me to watch this.” But she insisted, claiming this film was different. So, I gave her the benefit of the doubt and caved in. And she was right. I was enthralled from beginning to end. And I haven’t been sucked into another zombie flick in quite the same way ever since. That movie, Mr. Romero, was Dawn of the Dead.

George A. Romero: Oh! [Warm laughter].

Evelyn Reid: But why is that? What is it about the way you approach the concept that you brought to life yourself in 1968 of a flesh-eating corpse who returns from the dead? What is it about your approach that’s been so unique that no replication attempt seems to quite match your original?

George A. Romero: Oh, I think everybody is replicating it now. That’s part of the problem. [Laughter]. I don’t know… [pause]. I think it’s because my stories are less about the zombies and less about the threat and more about the human behavior [involved], more about the mistakes humans make, the stupid strategies that they employ. You know, they keep trying to live life like “the way it used to be” even when faced with this disaster. So I use [the zombie concept] to do political satire and social satire, stuff like that. But I do think that, first starting with Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead, the physical presentation of my zombies in those first several films, that is what survived. Like those zombie walks.

Evelyn Reid: So they took the superficial and ran with that but left the philosophical behind.

George A. Romero: Yeah. [Laughter].

Evelyn Reid: Now this is interesting to me because I am a huge film buff and horror movies were a major genre for me growing up in the ’80s and in the ’90s. I had seen every flick available for rental, except for a few zombie movies. [Laughter].

Above: the infamous pie scene in Dawn of the Dead (1978).

Evelyn Reid: But something has changed in recent years. Something started to shift around the mid to late ’90s and I don’t think it’s just with horror films. The film industry is rife with derivative, Mr. Romero. Films have bigger budgets than ever before and the special effects are spectacular, yet, something is missing in the story. Nuance. Complexity. Uncharted storylines. Why is the industry just doing the same thing over and over again?

George A. Romero: Well, that’s what they’re doing. [Laughter]. They’d rather bank on what they believe to be a sure thing or an old title, even if it didn’t make money the first time around. They’d rather bank on Texas Chainsaw Massacre 5 or Saw 7 than try to come up with something new, which is unpredictable. That is the problem. There’s no entrepreneurialism there at all. The studio executives, by and large, are trying to protect their careers and their jobs. The worst thing that can happen to you is that you have a bomb.

Evelyn Reid: Heads roll quickly in the industry.

George A. Romero: It takes a lot for somebody to come along with a fresh idea. I mean, right up until a couple of years ago, I was doing little zombie films. I made one film called Land of the Dead about nine years ago, which was a big budget production—$15 million—and yet I really found that I didn’t need it. I didn’t need [the big budget] at all. I really liked that film, it was successful, it got really good reviews but it didn’t make a lot of money and I really resented having one of the most expensive line items be Dennis Hopper’s cigars! I just said, man, I don’t need to do this. I’ll just go back to the roots. So I made two more films, Diary of the Dead and Survival of the Dead. One [budget] was $2 million and the other was $3 million bucks. And they were great! They actually made more money, they were more successful, and people liked them better. So I felt okay, but then along came The Walking Dead and then World War Z, and my God, you can’t sell “hey, I’m gonna make a little zombie movie, it’ll only cost $2-3 million” anymore. You have to spend $400 million or $200 million.

Evelyn Reid: You know, you think of The Blair Witch Project and its teeny budget back in the day, and no one expected it to become a huge hit. But it did.

George A. Romero: Yeah, it did.

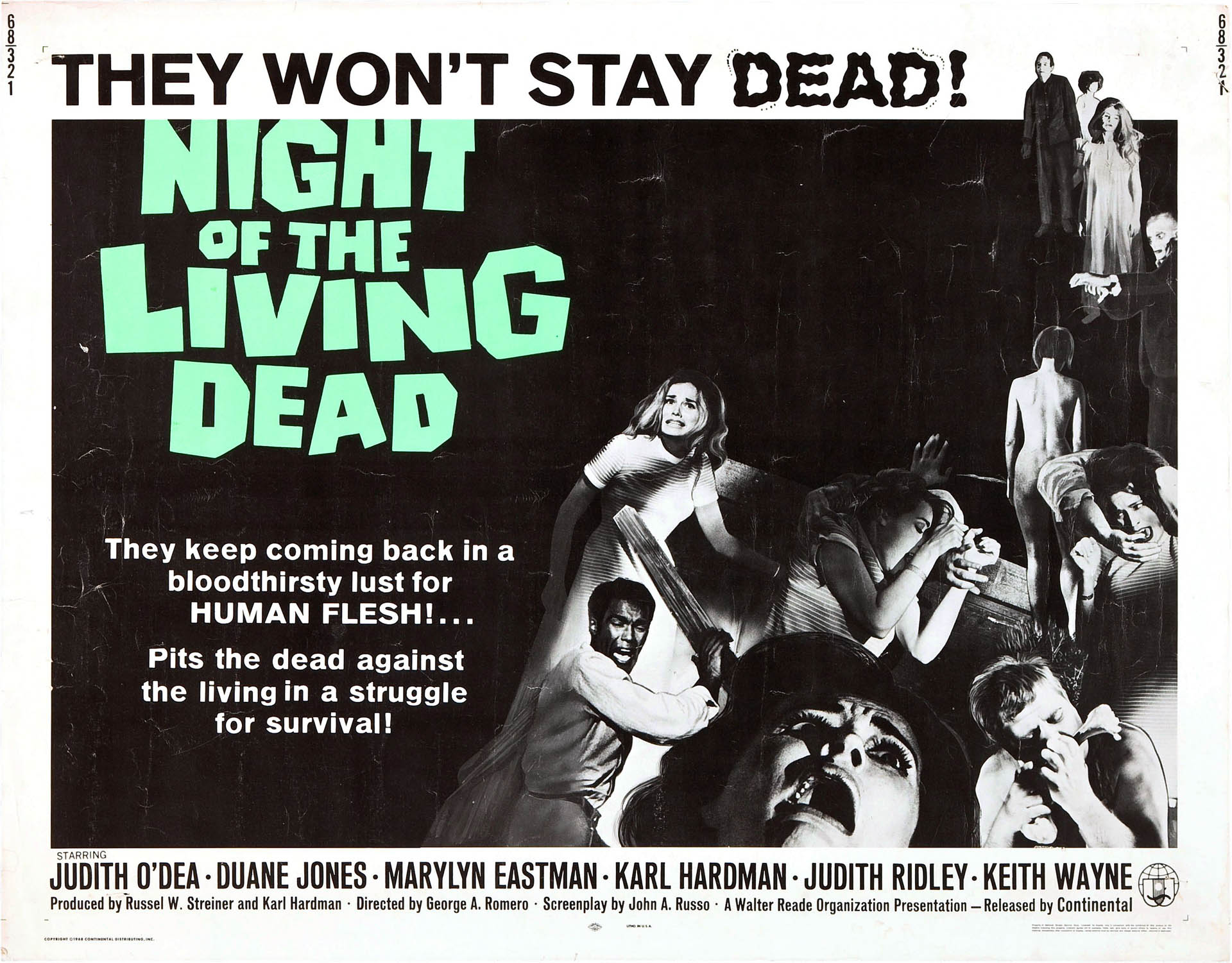

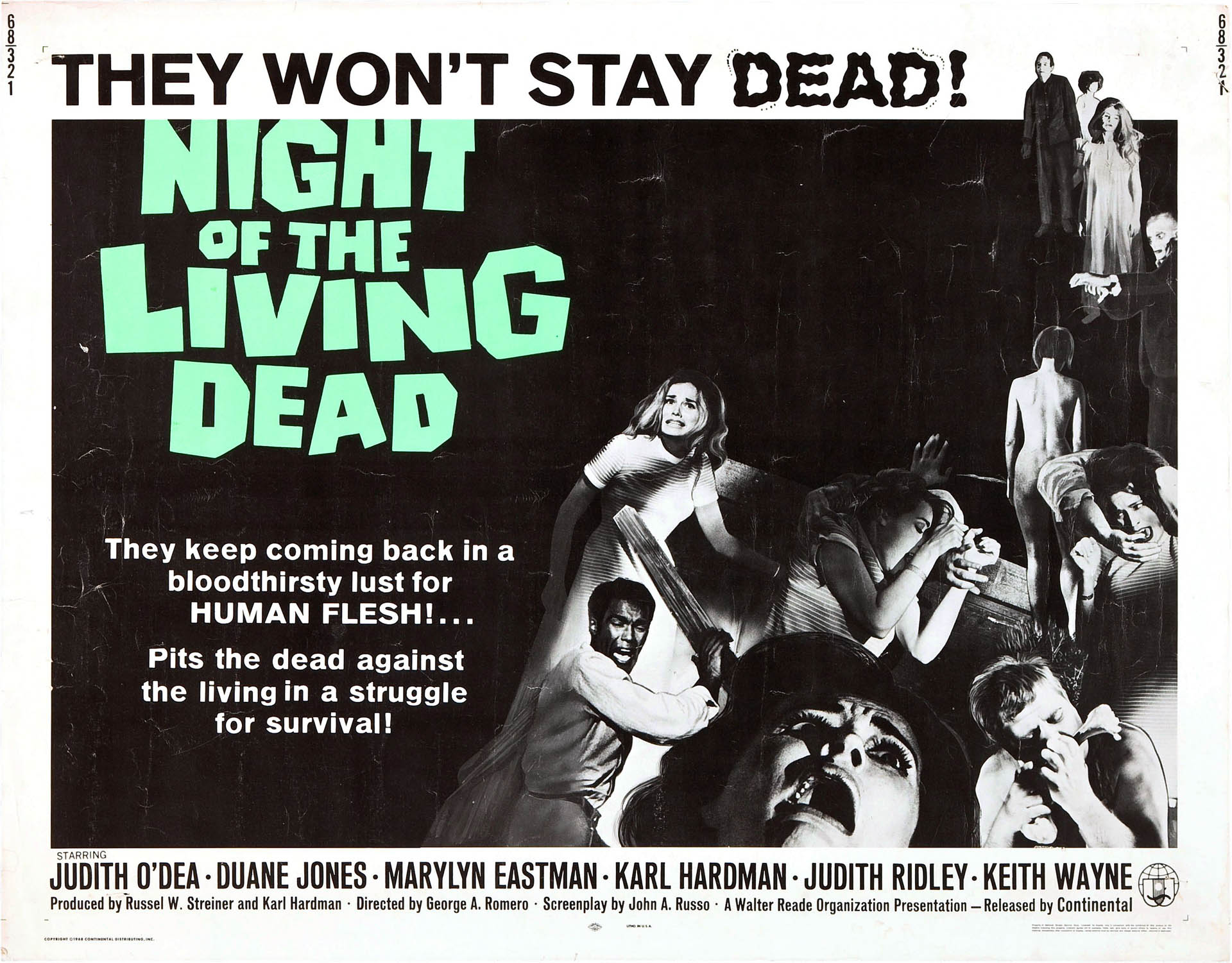

Above: Night of the Living Dead poster from 1968.

“The first thing I always say is DON’T make a zombie film!”

Evelyn Reid: Blair Witch was low risk, maybe $20,000 to make. I mean, is this something to be inspired by? Could there actually be a market for this? No executives would lose their shirts if a production like that bombs. Is there a way to circumvent the system to get back to your roots? Maybe even toy with 35mm again?

George A. Romero: Oh sure. I think there is. But I don’t think it’ll be with 35mm anymore. It will be some form of digital. You know, I do these conventions like this one in Montreal, the Comiccon, and every time I do one of these, young people come to me, young wannabe filmmakers who have made little films. Unfortunately, they’re always zombie films! [Roaring laughter]. But the first thing I always say is DON’T make a zombie film!

Evelyn Reid: [Laughter]. And the irony is you didn’t even call them zombies. And your flesh-eating undeads didn’t eat brains either. And they didn’t run around. Instead, they’re fragile corpses.

George A. Romero: My zombies have never eaten brains. That started in Return of the Living Dead and that wasn’t mine. Nah. I didn’t call them zombies. I didn’t think they were zombies.

Evelyn Reid: What were they supposed to be? How did you envision them in your mind’s eye?

George A. Romero: It was supposed to be unexplained. It was supposed to simply be that people are not staying dead. That’s it. That was it. I just wanted something that would be earth-shaking, like it should be, holy. It should be impressive enough to bring people up short. And yet those people are arguing should we stay upstairs, downstairs? They’re still arguing about their own agendas. And that’s what causes their downfall. They’re so wrapped up life-as-usual that they don’t even notice that the entire landscape and all the rules have changed. God changed the rules on us.

Above: Duane Jones in Night of the Living Dead (1978).

Evelyn Reid: But they’re not paying attention, too wrapped up in their little…

George A. Romero: …petty arguments. That’s what I wanted. That’s all I wanted. And I never thought it would become more than one film. And I didn’t make a second one for ten years. I had made a couple of other little films that didn’t go anywhere. But by then, everybody started to write about Night of the Living Dead as if it was some kind of important social comment. They were reading it as a racial comment, which it was never meant to be but of course became obvious as the lead character is an African American.

Evelyn Reid: In 1968, casting an African American as the lead and the hero was likely considered a bold, progressive move.

George A. Romero: But it was never meant to be a racial comment. It was never used as a theme, [his race] never comes up. They don’t argue over race. They argue over things that are much more petty. So that was that. Then, I said if I’m going to do another one… Italian filmmaker Dario Argento called me up and said, “please, let’s make another zombie film. I have money for it.” And coincidentally, I had just recently socially met the people who owned the shopping mall [that appears in Dawn of the Dead] and saw this “temple.” It was literally the first shopping mall in western Pennsylvania, the first we had ever seen. Now, they’re on every street corner but that was literally the first one that we’d ever seen. I said, “well here’s something.” And basically, I tried to do the same film but without the farmhouse.

Above: Buenos Aires’ Zombie Walk in 2009 (photo by Flickr user Beatrice Murch CC BY 2.0).

Evelyn Reid: Getting back to the premise that suddenly God changed the rules, there’s no more room in hell, and there are undead dead bodies everywhere… as you said, that was supposed to be left unexplained. Yet here we are decades later and fans want to know… why the rule change? Why is there suddenly no more room in the afterlife? Can fans look forward to an answer that question?

George A. Romero: Well, in The Walking Dead, it’s pretty ill-defined. I think they’re working on sort of the same premise. The tagline for Dawn of the Dead was “when there’s no more room in hell, then the dead will walk the earth.” I’ve been trying to sell that cow for six movies.

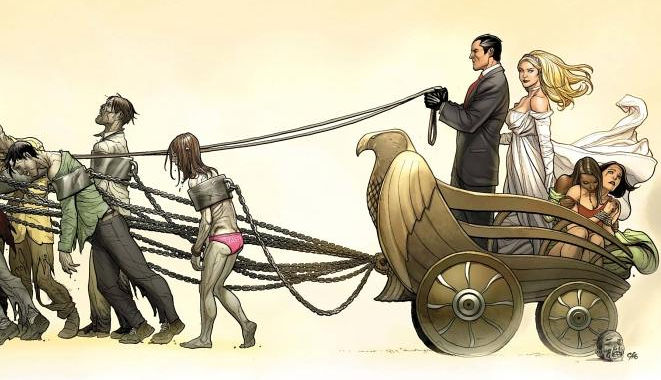

Evelyn Reid: [Laughter]. A lifetime, yeah. We’ve been talking a lot about the past, but I’d love to hear what you’re currently working on. I know you’ve got your comic book series, Empire of the Dead, that came out earlier in the year. What else is happening in your creative world?

George A. Romero: Well, I have a script that I just recently finished, The Zombie Autopsies, and I’m shopping it around right now. It’s based on a novel by a Harvard medical doctor named Steve Schlozman. And I adapted it into a screenplay. It’s a different kind of zombie. It’s a virus. Like a 28 Days Later kind of thing. And I have a comic zombie comedy thing I’m also trying to pitch. But right now, I’m focused on the comics. I have three more Empire of the Dead comics to write and we’re sort of hoping in the back of our minds maybe it can become a film or TV series.

Above: George A. Romero’s Marvel comic book series Empire of the Dead.

Evelyn Reid: Evelyn Reid: Anthologies like Creepshow and Tales from the Darkside (some of which I have on VHS at home, if you can believe it)… can we ever hope to see more of them from you? I miss that short story style format.

George A. Romero: Oh I love it too. And I think it’s sort of coming back now, but they were considered poison and still are by a lot of people. I don’t know why.

Evelyn Reid: Were there financial losses with previous anthologies?

George A. Romero: Well not so much losses. Creepshow was the only film I ever made that hit #1 on the charts! I don’t think that it was that the films didn’t do well. It’s just that it costs so much.

Evelyn Reid: All the different sets, the casting, the incessant coordination…

George A. Romero: Yeah, everything. It’s like making five films in one.

Evelyn Reid: Sounds exhausting.

George A. Romero: Yeah. And also, in terms of TV, no one wants to do TV anthologies because they want standing sets. They want to be able to reuse everything, reuse their characters.

Evelyn Reid: Rinse and repeat. Save time and money. A recurring theme, ennit.

George A. Romero: Yeah.

George A. Romero: The Zombie Godfather

by Evelyn Reid

Originally published on About.com September 9, 2014

Above: “zombie” participant at the 2013 edition of the Montreal Zombie Walk (photo by Flickr user Franck BLAIS (CC BY-SA 2.0)).

Name drop “George A. Romero” on any given day and anticipate chatter of zombies to follow suit. Yet if you ask the “zombie godfather” his take, he’ll tell you he never set out to have his undead concept infect pop culture so pervasively, if the proliferation of urban zombie walks, zombie video games, and a wildly successful primetime series are any indication that the zombie apocalypse is here to stay.

If anything, he’s concerned the notion of a reanimated corpse schlepping along is a tired narrative. “I used to be the only guy in the playground,” he said in a 2013 Telegraph interview entitled “Why I Don’t Like The Walking Dead.” His disappointment vis-à-vis the horror drama series is no secret. Whether the let-down is fueled by the fact that Romero barely earned a penny from his opus of opuses due to a copyright fumble that catapulted Night of the Living Dead into the public domain decades before its time is possible and plausible, however speculative.

So on the eve of his Montreal Comiccon appearance, I sat down with the writer/director for a session of proverbial brain picking, if only for the chance to see today’s film industry through the eyes of a film legend who lived to tell the tale of the golden age of horror.

Above: George A. Romero (photo courtesy of George A. Romero).

Evelyn Reid: You know, I wasn’t into zombies growing up. Apart from those featured in Michael Jackson’s infamous “Thriller” video, they did nothing for me. I found them boring and mindless, no pun. Then one day in college a friend wanted to show me a movie, a zombie flick. I looked at her, discouraged, saying, “you’d have to pay me to watch this.” But she insisted, claiming this film was different. So, I gave her the benefit of the doubt and caved in. And she was right. I was enthralled from beginning to end. And I haven’t been sucked into another zombie flick in quite the same way ever since. That movie, Mr. Romero, was Dawn of the Dead.

George A. Romero: Oh! [Warm laughter].

Evelyn Reid: But why is that? What is it about the way you approach the concept that you brought to life yourself in 1968 of a flesh-eating corpse who returns from the dead? What is it about your approach that’s been so unique that no replication attempt seems to quite match your original?

“The first thing I always say is DON’T make a zombie film!”

George A. Romero: Oh, I think everybody is replicating it now. That’s part of the problem. [Laughter]. I don’t know… [pause]. I think it’s because my stories are less about the zombies and less about the threat and more about the human behavior [involved], more about the mistakes humans make, the stupid strategies that they employ. You know, they keep trying to live life like “the way it used to be” even when faced with this disaster. So I use [the zombie concept] to do political satire and social satire, stuff like that. But I do think that, first starting with Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead, the physical presentation of my zombies in those first several films, that is what survived. Like those zombie walks.

Evelyn Reid: So they took the superficial and ran with that but left the philosophical behind.

George A. Romero: Yeah. [Laughter].

Evelyn Reid: Now this is interesting to me because I am a huge film buff and horror movies were a major genre for me growing up in the ’80s and in the ’90s. I had seen every flick available for rental, except for a few zombie movies. [Laughter].

Above: the infamous pie scene in Dawn of the Dead (1978).

Evelyn Reid: But something has changed in recent years. Something started to shift around the mid to late ’90s and I don’t think it’s just with horror films. The film industry is rife with derivative, Mr. Romero. Films have bigger budgets than ever before and the special effects are spectacular, yet, something is missing in the story. Nuance. Complexity. Uncharted storylines. Why is the industry just doing the same thing over and over again?

George A. Romero: Well, that’s what they’re doing. [Laughter]. They’d rather bank on what they believe to be a sure thing or an old title, even if it didn’t make money the first time around. They’d rather bank on Texas Chainsaw Massacre 5 or Saw 7 than try to come up with something new, which is unpredictable. That is the problem. There’s no entrepreneurialism there at all. The studio executives, by and large, are trying to protect their careers and their jobs. The worst thing that can happen to you is that you have a bomb.

Evelyn Reid: Heads roll quickly in the industry.

George A. Romero: It takes a lot for somebody to come along with a fresh idea. I mean, right up until a couple of years ago, I was doing little zombie films. I made one film called Land of the Dead about nine years ago, which was a big budget production—$15 million—and yet I really found that I didn’t need it. I didn’t need [the big budget] at all. I really liked that film, it was successful, it got really good reviews but it didn’t make a lot of money and I really resented having one of the most expensive line items be Dennis Hopper’s cigars! I just said, man, I don’t need to do this. I’ll just go back to the roots. So I made two more films, Diary of the Dead and Survival of the Dead. One [budget] was $2 million and the other was $3 million bucks. And they were great! They actually made more money, they were more successful, and people liked them better. So I felt okay, but then along came The Walking Dead and then World War Z, and my God, you can’t sell “hey, I’m gonna make a little zombie movie, it’ll only cost $2-3 million” anymore. You have to spend $400 million or $200 million.

Evelyn Reid: You know, you think of The Blair Witch Project and its teeny budget back in the day, and no one expected it to become a huge hit. But it did.

George A. Romero: Yeah, it did.

Evelyn Reid: Blair Witch was low risk, maybe $20,000 to make. I mean, is this something to be inspired by? Could there actually be a market for this? No executives would lose their shirts if a production like that bombs. Is there a way to circumvent the system to get back to your roots? Maybe even toy with 35mm again?

George A. Romero: Oh sure. I think there is. But I don’t think it’ll be with 35mm anymore. It will be some form of digital. You know, I do these conventions like this one in Montreal, the Comiccon, and every time I do one of these, young people come to me, young wannabe filmmakers who have made little films. Unfortunately, they’re always zombie films! [Roaring laughter]. But the first thing I always say is DON’T make a zombie film!

Evelyn Reid: [Laughter]. And the irony is you didn’t even call them zombies. And your flesh-eating undeads didn’t eat brains either. And they didn’t run around. Instead, they’re fragile corpses.

Above: Night of the Living Dead poster from 1968.

George A. Romero: My zombies have never eaten brains. That started in Return of the Living Dead and that wasn’t mine. Nah. I didn’t call them zombies. I didn’t think they were zombies.

Evelyn Reid: What were they supposed to be? How did you envision them in your mind’s eye?

George A. Romero: It was supposed to be unexplained. It was supposed to simply be that people are not staying dead. That’s it. That was it. I just wanted something that would be earth-shaking, like it should be, holy. It should be impressive enough to bring people up short. And yet those people are arguing should we stay upstairs, downstairs? They’re still arguing about their own agendas. And that’s what causes their downfall. They’re so wrapped up life-as-usual that they don’t even notice that the entire landscape and all the rules have changed. God changed the rules on us.

Evelyn Reid: But they’re not paying attention, too wrapped up in their little…

George A. Romero: …petty arguments. That’s what I wanted. That’s all I wanted. And I never thought it would become more than one film. And I didn’t make a second one for ten years. I had made a couple of other little films that didn’t go anywhere. But by then, everybody started to write about Night of the Living Dead as if it was some kind of important social comment. They were reading it as a racial comment, which it was never meant to be but of course became obvious as the lead character is an African American.

Evelyn Reid: In 1968, casting an African American as the lead and the hero was likely considered a bold, progressive move.

George A. Romero: But it was never meant to be a racial comment. It was never used as a theme, [his race] never comes up. They don’t argue over race. They argue over things that are much more petty. So that was that. Then, I said if I’m going to do another one… Italian filmmaker Dario Argento called me up and said, “please, let’s make another zombie film. I have money for it.” And coincidentally, I had just recently socially met the people who owned the shopping mall [that appears in Dawn of the Dead] and saw this “temple.” It was literally the first shopping mall in western Pennsylvania, the first we had ever seen. Now, they’re on every street corner but that was literally the first one that we’d ever seen. I said, “well here’s something.” And basically, I tried to do the same film but without the farmhouse.

Above: Duane Jones in Night of the Living Dead (1978).

Evelyn Reid: Getting back to the premise that suddenly God changed the rules, there’s no more room in hell, and there are undead dead bodies everywhere… as you said, that was supposed to be left unexplained. Yet here we are decades later and fans want to know… why the rule change? Why is there suddenly no more room in the afterlife? Can fans look forward to an answer that question?

George A. Romero: Well, in The Walking Dead, it’s pretty ill-defined. I think they’re working on sort of the same premise. The tagline for Dawn of the Dead was “when there’s no more room in hell, then the dead will walk the earth.” I’ve been trying to sell that cow for six movies.

Evelyn Reid: [Laughter]. A lifetime, yeah. We’ve been talking a lot about the past, but I’d love to hear what you’re currently working on. I know you’ve got your comic book series, Empire of the Dead, that came out earlier in the year. What else is happening in your creative world?

George A. Romero: Well, I have a script that I just recently finished, The Zombie Autopsies, and I’m shopping it around right now. It’s based on a novel by a Harvard medical doctor named Steve Schlozman. And I adapted it into a screenplay. It’s a different kind of zombie. It’s a virus. Like a 28 Days Later kind of thing. And I have a comic zombie comedy thing I’m also trying to pitch. But right now, I’m focused on the comics. I have three more Empire of the Dead comics to write and we’re sort of hoping in the back of our minds maybe it can become a film or TV series.

Above: George A. Romero’s Marvel comic book series Empire of the Dead.

Evelyn Reid: Anthologies like Creepshow and Tales from the Darkside (some of which I have on VHS at home, if you can believe it)… can we ever hope to see more of them from you? I miss that short story style format.

George A. Romero: Oh I love it too. And I think it’s sort of coming back now, but they were considered poison and still are by a lot of people. I don’t know why.

Evelyn Reid: Were there financial losses with previous anthologies?

George A. Romero: Well not so much losses. Creepshow was the only film I ever made that hit #1 on the charts! I don’t think that it was that the films didn’t do well. It’s just that it costs so much.

Evelyn Reid: All the different sets, the casting, the incessant coordination…

George A. Romero: Yeah, everything. It’s like making five films in one.

Evelyn Reid: Sounds exhausting.

George A. Romero: Yeah. And also, in terms of TV, no one wants to do TV anthologies because they want standing sets. They want to be able to reuse everything, reuse their characters.

Evelyn Reid: Rinse and repeat. Save time and money. A recurring theme, ennit.

George A. Romero: Yeah.